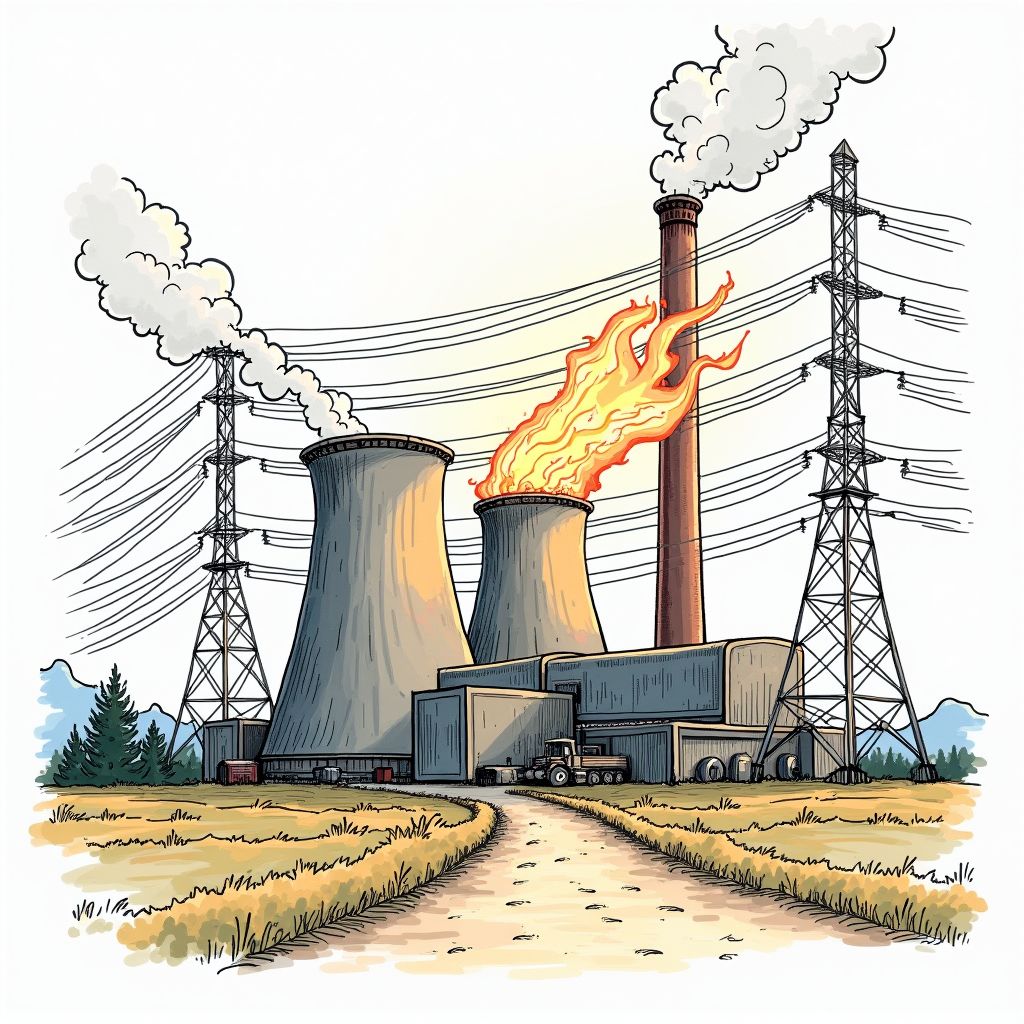

EPA Blocks Colorado's Coal Plant Shutdowns Over Grid Stability Concerns

Denver, Saturday, 10 January 2026.

On January 9, 2026, the EPA formally rejected Colorado’s regional haze reduction plan, which relied on the early retirement of coal-fired power plants. Signaling a regulatory pivot toward infrastructure stability, the agency determined that these facilities are critical for maintaining grid reliability amidst growing energy demands. This decision effectively halts the state’s decarbonization timeline, forcing Colorado to draft a new compliance strategy within two years or face a federally imposed plan. The ruling underscores the intensifying friction between state environmental mandates and the federal prioritization of energy security and baseload capacity.

Federal Intervention and Legal Rationale

The EPA’s rejection, finalized on Friday, January 9, 2026, centers on Colorado’s Regional Haze State Implementation Plan, which federal regulators argue violates the Clean Air Act [1][2]. Specifically, the agency cited the state’s attempt to mandate the retirement of coal-fired units—such as Colorado Springs Utilities’ Nixon Unit 1—without securing the necessary consent from the facilities themselves [1][2]. EPA Region 8 Administrator Cyrus Western emphasized that while the state could have kept these plants operational and still met air quality standards, it opted to force closures, a move the agency characterized as placing the desire to shutter plants above federal law [2]. The decision halts the state’s plan to close its remaining coal-fired electricity generation plants by 2031, a timeline that state officials had established to meet greenhouse gas reduction goals [2].

Grid Reliability vs. Haze Reduction

This regulatory intervention aligns with the Trump administration’s broader energy strategy, which prioritizes the preservation of baseload power sources to meet rising electricity consumption [1]. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin stated that reliable baseload energy is essential for “Powering the Great American Comeback,” explicitly linking the decision to the need for cost-effective energy for families [1][6]. The administration has pointed to the surging energy demands from data centers and artificial intelligence infrastructure as a key driver for maintaining existing coal capacity, arguing that the premature retirement of these assets poses a risk to grid stability [1]. Consequently, the EPA rejected the notion that voluntary retirements included in the state’s plan were sufficient to guarantee reliability [4].

Infrastructure Constraints and Facility Specifics

The conflict highlights specific facilities where operational timelines are now in flux. The EPA’s disapproval heavily weighed the status of the Nixon Unit 1 plant, which was scheduled for closure in 2029 [2][6]. Regional administrator Western noted that Colorado Springs Utilities had expressed a desire to keep the unit operational beyond that date, contrary to the state’s plan [2]. Additionally, the Department of Energy had already intervened in the sector earlier in the winter, issuing an emergency order in December 2025 to keep Unit 1 of the Craig Station coal plant online through March 30, 2026, citing potential regional power shortfalls [1][6]. This pattern of federal intervention suggests a concerted effort to override state-level decarbonization schedules in favor of extending the lifespan of fossil fuel infrastructure [7].

Economic Implications and Cost Arguments

While the EPA argues that keeping these plants online ensures reliability, environmental advocacy groups and state officials contend that the move will burden ratepayers. Analysis cited by the Sierra Club suggests that maintaining operations at Craig Station Unit 1 could cost ratepayers approximately $20 million over a 90-day period, or between $85 million and $150 million annually [4]. Michael Hiatt of Earthjustice criticized the administration’s stance as an “ideological attack,” arguing that clean energy alternatives in Colorado are far cheaper than continuing to run what he described as “expensive, dirty, and unreliable” coal infrastructure [4]. Critics further argue that the decision threatens the visitor experience at national parks like Rocky Mountain and Great Sand Dunes, where haze pollution remains a significant concern [3][4].

Political Fallout and State Response

The decision has ignited a sharp exchange between Colorado’s Democratic leadership and the federal administration. Governor Jared Polis condemned the ruling, stating that the Trump administration had chosen “dirtier air and higher costs” over the state’s carefully crafted utility plans [6]. Polis argued that the federal decision is “out of touch with the realities of the electric grid,” noting that utilities had voluntarily planned these retirements to transition to lower-cost resources like wind and solar [6]. State air quality officials echoed this sentiment, asserting that the retirement dates align with market realities and utility planning [5]. Conversely, the Colorado Mining Association welcomed the decision as “prudent,” agreeing with the EPA that the state had failed to adequately consider the negative impacts on grid reliability [5]. With the rejection now formalized, Colorado faces a strict timeline: the state must submit a revised, approvable implementation plan within two years, or the EPA will invoke its authority to implement a federal plan [2].

Sources

- www.reuters.com

- coloradosun.com

- earthjustice.org

- www.sierraclub.org

- gazette.com

- www.washingtonexaminer.com

- news.bloomberglaw.com